COVID-19 continues to spread across the US, with Brazil and India following in the highest number of cases of the virus. From getting married over Zoom to walking dogs with a drone, the pandemic has already shattered many assumptions we had about living our daily lives. While it is too soon to fully realize what the lasting consequences from these past months will be (socially, economically, mentally, politically), there are some changes that have already impacted how we see the climate crisis and discuss strategies to lower contributions to greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). What could the impacts of these behavioral resets look like? We talk through three of them below.

1. The possibility of working remotely is now a viable option for many professions.

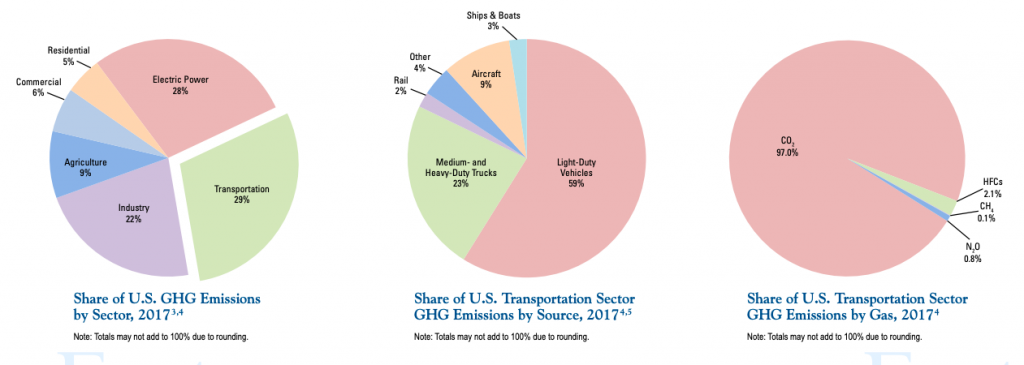

According to an article for Quartz at Work, “Because so many occupations in the United States are information-based, nearly 37% of jobs can now be accomplished remotely.” It is also predicted that “incentivizing these employees to work from home just two or three days a week will reduce their typical commute-based greenhouse gas emissions by half, immediately.” If you’ve ever passed through a rush hour in any major US city, you are well aware of the fact that you could be sitting in your car in a line of traffic for hours without moving more than a mile. Not only is it endlessly frustrating, but it is needlessly wasteful and contributes massively to ‘every-day pollution’. According to the EPA, “transportation accounted for the largest portion (29%) of total U.S. GHG emissions in 2017. Cars, trucks, commercial aircraft, and railroads, among other sources, all contribute to transportation end-use sector emissions.” Light-duty cars, like passenger vehicles, made up the majority of that percentage. Working remotely is not an option for many professions. However, for the jobs where it is possible, something made visible during the stay-at-home precautionary policies, reducing the days that one commutes to work could limit your contribution to climate change as well as increase productivity (with healthy boundaries), expand job pools, take the social stress off of introverts, and increase job options for families.

2. Expanding activism to include online spaces as well as physical ones.

Online activism has not always been popular, with some going as far as calling it slacktivism because it requires less energy than picking up pollution on a beach or bringing compost to a collection point, for example. However, as a consequence of social distancing, many environmental conferences, marches, and social justice movements have had to establish themselves online. While online activism is not a substitute for the energy and support experienced in community gatherings, it can provide a way to spread valuable information to movements that span across massive geographical boundaries. It is most effective when online activism inspires offline action and can help evade censorship in countries where newspapers face more severe government control. There are many concerns with online activism, particularly social media censorship and being buried in waves of disinformation campaigns. But as this forced and drastic transition to digital continues to evolve, the capacity to connect people across continents to discuss solutions to global problems, all without booking a plane flight, can impact environmental activism impressively

3. This pandemic shows us just how important ‘multisolving’ is.

Multisolving refers to the fact that we can’t just tackle one issue at a time like a daily to-do list. By addressing multiple issues at once, solutions can be more effective for each individual crisis we face. Protests and marches against racial inequality have flourished across the country with individual industries analyzing how their own inactiveness contributes to systemic racism. Beyond this, the global pandemic has unequally impacted low income communities that are already unequally facing the impacts of climate change.

We cannot afford to go back to the world we had before this crisis. That would mean leaving unaddressed the vulnerabilities and fragilities that this crisis has brought into plain sight: massive underinvestment in health and social protection; massive global and local inequalities; the onward march towards the destruction of nature and climate catastrophe; the erosion of democratic norms that are core to protecting rights and ensuring social cohesion.

Amina Mohammed, UN Deputy Secretary-General to the United Nations in May

Perhaps one of the most startling points realized during this global health crisis is behavioral change. Amina Mohammed continued that, “This crisis has already demonstrated that massive change can be brought about if there is political will and unity of purpose.” This year has already been an apocalyptic hellscape for countries across the world. Now it is necessary that when we return to some kind of ‘normal’, we make that normal a healthier, more equal, anti-racist, safer, greener version than we had before.

Food

Food Farmers

Farmers Sustainable Living

Sustainable Living Living Planet

Living Planet News

News