Oyster restoration projects have recently been making waves in the conversation around sustainability, especially in coastal New England towns and cities. Over the past decade or so, teams of dedicated scientists and environmentalists have been working hard in places like New York City and Boston to revitalize the once thriving oyster populations that filled their waters hundreds of years ago. It seemed only fitting to sit down with Chris Teufel, an oyster farmer and aquaculture enthusiast, for July’s 18 Questions. Follow along with us as we learn about his work at Island Creek Oysters in Duxbury, Massachusetts, and how marine life such as oysters, scallops, sea urchins, and kelp might hold the key to a food-secure future.

- What first piqued your interest in oysters and aquaculture?

I saw aquaculture for the first time during my sophomore year in high school, when I was participating in a program in the Bahamas, where they had a closed-loop, aquaponic operation between tilapia and plants like lettuce and tomatoes. They used the waste from the fish to fertilize the plants, which grew quickly in the water. I found oysters at the Duke Marine Lab, where I worked under a professor to help set up an oyster project on an unused plot of land that had been donated several decades ago.

- Describe the value of oyster farming in the context of building a sustainable food system.

There is no need for arid land, which is in high demand for monoculture crops. Instead, we grow oysters in biodiverse marine environments that can support high densities of oyster populations. In fact, an aquaculture farm the size of Rhode Island could feed the entire United States. Additionally, while fresh water will become more of a concern in the future, oyster farming does not require any. Oyster farming has minimal carbon emissions, making it one of the very few animal-based protein operations that can have a net benefit on the environment. The gas that takes our boats to and from the farm is virtually our only source of carbon emissions, and we could transition to electric motors in the future.

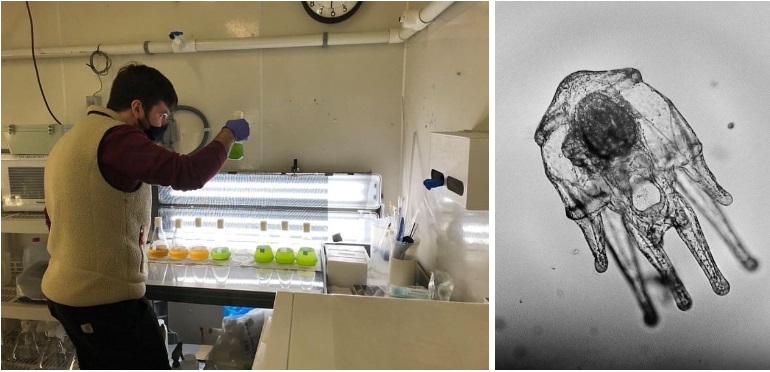

Right: Oyster seed grown at hatchery

- What makes oysters ideal for preserving and rebuilding marine ecosystems?

Adult oysters can filter up to 50 gallons of water each day, reducing nitrogen and curbing the algae blooms that have become so common with runoff in New England. Sometimes we release smaller oysters into the wild, and sometimes they are inevitably blown off the farm during major storms, and this dispersal can help nurture wild oyster reefs.

- How has Island Creek Oysters impacted its local environment?

We are working with Northeastern University in Boston to get more of a quantitative analysis of our impact on the environment. However, it has long been known that the farm attracts greater biodiversity than the surrounding areas. Furthermore, we have found that the farm also acts as a nursery ground for sea life before organisms are ready to move out to deeper waters. Many species are essential for the ecosystem and often commercially relevant for fishing operations that have seen their populations decline in the past.

- When did the oyster population begin to decrease in the Massachusetts waters?

Between the 1800s and 1900s, oyster populations in Massachusetts began to suffer. There was once a thriving oyster ecosystem and massive oyster bars for hungry diners, but factors like pollution and overharvesting have decimated their populations. A similar trend occurred in nearby New York City, which used to be the world’s oyster capital. Building back oyster reefs is vital to supporting our state’s lands and waters; oyster reefs are great coastal buffers, support rich ecosystems, and naturally reduce ocean acidification.

- You are currently the nursery manager at Island Creek Oysters. Describe what that job entails.

It changes with the season. Currently, I am out in the nursery. Our main goal is to move the oysters from the hatchery, which can be as tiny as grains of sand, to the farm itself once they have reached about 1 ½ inches. We protect them in tanks called upwellers, where they get their first taste of ocean water, and I clean the upwellers a few times each day. We sort small oysters from large ones and take them to floating cages in the river. There, we place them in mesh bags that keep them secure while allowing them to feed and filter water. After that, they are put through a grater (we call ours “Bubba”), where they are sorted by size and sprayed with fresh water to help kill bacteria. We are working on a system to use just salt water instead. We will put them back in bags, after which some are taken to bottom cages. As soon as they are ready, we swap out the bags for ones with larger mesh to allow them to grow faster and healthier. Then the oysters can go out to our farm, where they spend their final months growing.

- What did your previous jobs look like at Island Creek Oysters?

I started out as a farm hand, helping a few different crews and learning the ropes. Last winter, I was able to work in the hatchery as a technician with an almost entirely female team. We would study the oysters, clams, and scallops under microscopes. We would also grow algae, which is essential to the hatchery, in what looks like a little kid’s imagination of a scientific laboratory, with colorful vats of bubbling liquid. Since May, I have been the nursery manager overseeing a summer crew of high school and college students.

Right: The “k-tube room,” containing fiberglass tubes of algae used to feed the oysters. The funnel is connected to a hose that runs down through the floor to the larval tanks for easier feeding.

- How do weather patterns impact your day-to-day functions?

We have to pay close attention to the weather and tides throughout the day and prepare accordingly. If the tide is too high, we may have to work with water up to our chests, and accessing oysters on the bottom is more challenging. At other times, we can pick oysters right off the mud.

- What is it like to work in the winter?

The bay can get very cold, and we definitely have to wear life jackets, bundle up, and try to patch the holes in our waders. Sometimes we break through the ice to get out to the farm. We keep some oysters in the water and some on land for the roughest part of winter. They can survive out of water for up to a month or so. The problem for the oysters is not necessarily the cold but the ice shards that can lacerate them on the inside. Taking them onto land is pretty unique to this area. For instance, up in Maine, they typically sink their gear.

- How has your work with oysters impacted the way you view food in general?

Working with oysters has made me far more appreciative of all the work that goes into producing any kind of food and more aware of how little people know about most of the farming practices that provide them with what they eat daily. I have always tried – albeit somewhat passively in the past – to learn where my food comes from and where the ingredients are being sourced. However, working in food production has taken that to the next level. I have loved getting sustainably sourced shellfish, seaweed, and even fish and not having to step foot in a grocery store for weeks at a time.

However, in terms of fixing our broken food production and distribution system and global supply chain, I think it all starts with buying more food from local purveyors and small farms. It does help to know people who work on farms and live in a prime location, which unfortunately is not currently very accessible for many people. But I dream about it with my coworkers from time to time: everyone getting back to living off the land or having better systems for growing fresh food near big cities and metropolitan areas. I am always working towards being better at sourcing my food sustainably.

- Tell us something commonly misunderstood about oysters or a question you often get from people visiting the farm.

Some people wrongly assume oyster farms are bad for the environment. This perspective typically stems from the bad rap that has been given to large-scale fisheries. But while fisheries have put a heavy strain on the ocean habitat, oyster farming does the reverse: it cleans up pollution. It is the same with land plants; some crops and farms are more environmentally friendly than others.

- Describe your research on green sea urchins.

I was a research assistant at the Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research in Franklin, Maine, where we studied green sea urchins to try to restore their wild populations and understand their relationship with oysters and kelp. The three have the potential to work together in a healthy ecosystem. For instance, sea urchins can feed on biofouling (seaweed, barnacles, and other lifeforms accumulated on oyster cages over time) and clean them, while kelp can filter the water and reduce ocean acidification to support the other two species.

Right: Larval sea urchin

- You have worked in many parts of the ocean – from Cape Town to coastal North Carolina to the northeastern region of the United States. What has this range of experience taught you?

I have learned to appreciate the not-so-charismatic species. I got into marine biology the same way as many others: I was fascinated by megafaunas like whales, sea turtles, and sharks that get much media attention and conservation money. However, working with invertebrates and shellfish, I have learned how essential they are for the environment. I feel like I am seeing a whole new world that most people don’t know about.

- What is the relationship between Island Creek Oysters and the surrounding community?

For the most part, our community has rallied around us. There are now 27 farms throughout the bay, and people tend to give them their space. People sometimes dislike seeing workers on the water or farms amidst their beautiful ocean views. So we always try to be nice to our neighbors and develop good relationships with them.

- Can distant communities (i.e., the Midwest) also support these projects?

There are now land-based aquaculture systems, especially for fish. Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) currently use a significant amount of energy, but they are becoming more sustainable and will likely be highly relevant in the future. Some use salt water, while others use fresh. With water being recirculated, no addition of water is necessary.

- What distinguishes oysters from one farm to another?

Many people are working on the flavor analysis of oysters. Similar to the fine wine culture and its concept of terroir. Oysters have merroir, hailing from the French word mer, meaning “sea.” Farm to farm and region to region, oysters are eating different types of algae and experiencing different tidal flows. Even within our farm, the same species of oysters can taste differently depending on the area in which they are grown. Even living half a mile away from one another over six months makes a difference in taste.

- What is your favorite way to eat oysters?

I like them raw in the half shell, with mignonette – a little bit of red wine vinegar or champagne vinegar with some shallots and pepper. I like to eat one straight up, with nothing on it, then one with lemon, then the rest with mignonette. Eating them raw in the half shell allows me to experience the merroir I mentioned earlier.

- Why do you do what you do?

I love being out on the farm and the hands-on relationship that goes into every single oyster. Aquaculture and oyster farming have been part of my life for many years, and I don’t see them going away soon. They’re my babies.

Food

Food Farmers

Farmers Sustainable Living

Sustainable Living Living Planet

Living Planet News

News