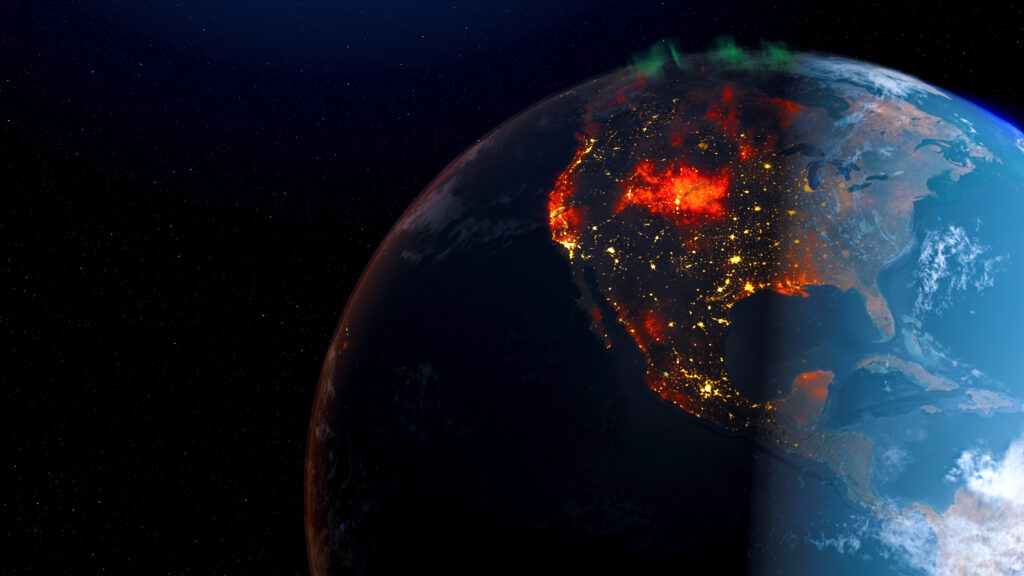

This week is Fire Prevention Week, and though we may not all experience a fire in our own homes, wildfires are disasters that can indirectly affect us all. A decade ago, climate change was a somewhat abstract notion, but today it’s a reality worldwide. Western states especially have endured wildfires exacerbated by the effects of climate change; so far this year, they have experienced 46,091 fires raging over 5,907,288 acres. Wildfires in California infamously outstrip any other state in magnitude. From the beginning of July until the middle of September, California’s wildfire season was in full force, burning more than 2.4 million acres, an area larger than the Grand Canyon. But even the fires of California pale in comparison to the fires of Siberia. Extreme heatwaves and drought have contributed to wildfires in Siberia on such a large scale that they are burning across more acreage than all the other wildfires in the world combined: 39,680,000 acres, to be precise.

Not only do wildfires forcibly evict people from their homes and ravage the landscape, but they also destroy countless animals’ natural habitats, wipe out historically significant natural areas, and leach chemicals into drinking water. Scientists have known for years that runoff from burned homes can put harmful chemicals into groundwater and reservoirs. But research in the aftermath of the 2017 wildfires in wine country north of San Francisco and the 2018 fire that destroyed the town of Paradise in the foothills of the Sierra discovered a different threat: Benzene and other dangerous contaminants were found inside water systems, possibly from heat-damaged plastics in the water infrastructure.

The billowing smoke of wildfires also induces health problems for people miles away, particularly those with asthma or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). The smoke itself is a mixture of gases and particles like volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, soot, and ash. Right away, it can cause watery eyes and scratchy throats. But the biggest threats from smoke coming from some of the tiniest particles, particularly those with a diameter smaller than 2.5 microns, known as PM2.5. These particles can penetrate deep into the airways, exacerbating heart, and lung problems. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued statements warning that people with Covid-19 are at increased risk from wildfire smoke during a pandemic.

How do these wildfires come about? There is a wide range of “first sparks,” including lightning strikes, arson, machinery, campfires, and cigarette butts. Hot temperatures combined with drought provide the dryness that allows wildfires to thrive. According to climate scientists, the warmer and drier conditions create drier fuel, and fundamentally the science is very, very simple. What would have been a fire easily extinguished now just grows very quickly and becomes out of control. Oftentimes, fires merge, creating blazes so large that they are dubbed “megafires,” and if they burn over 1 million acres, they are called “gigafires.”

Although they are termed “natural disasters,” 85-90% of wildfires in the United States are actually caused by human behavior. Even the ones that are naturally induced are made monstrous by the greenhouse gases released from human activity. The burning of fossil fuels like coal and oil has released greenhouse gases that increase temperatures, desiccating forests and priming them to burn. The numbers are clear: since 2000, twice as much land has burned in the United States each year on average than did in the 1990s.

So what can we do?

In the short term, evacuation support is needed to help those affected by the burns seek shelter and care. The Center for Disaster Philanthropy categorizes two phases of aid: response and recovery. During the response phase, victims need temporary shelter, food, water, hygiene supplies, animal support, cash, and livelihood assistance. During the recovery phase, they need help rebuilding or repairing their homes, cleaning up debris, treating the soil, caring for their mental and physical health, and more.

But to prevent wildfires in the first place, we need to take a more proactive stance. We need to support drought mitigation programs, such as water conservation, proper land development, and sustainable agriculture. We need to be more mindful of how we use and store flammable materials. And we need to fight climate change on a more holistic, integrated platform that recognizes the interconnectedness of all environmental disasters and human activity.

Food

Food Farmers

Farmers Sustainable Living

Sustainable Living Living Planet

Living Planet News

News