Last year, history was being made while answering questions we didn’t think to ask. We’re used to Google having all the answers, but it’s easier to forget just how difficult some of these questions are. For instance, this question took a harrowing journey through wind, water, and rain (with the possibility of scaling a cliff, too) before it could be answered: what is the southernmost tree in the world?

While it might only be an extremely challenging trivia question for most, the identification of the southernmost tree on the planet establishes an integral data point in climate change research. As the South Pole and Antarctica warm, vegetation that historically grow closer to the equator could begin populating the regions closer to the poles. When summers begin earlier and winters are shorter, “Changes in the timing of these events — spring thaw or songbird migration, for example — can have adverse effects on ecosystems, because different species may respond to different environmental cues, resulting in a misalignment between species that may rely on one another.” Entire ecosystems could shift, as the species that cannot adapt quickly enough fade away and others migrate to follow their food sources. The ultimate result could be that “interdependent species may become separate as their environment changes” and the species of flora and fauna that can move, will.

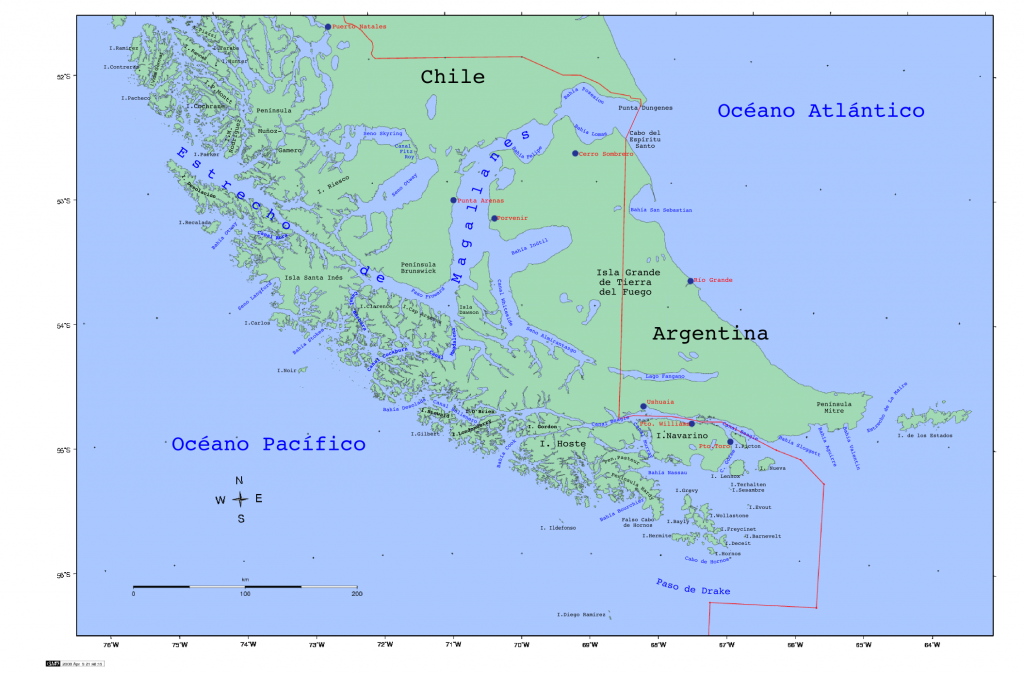

Research is already indicating this shift. In a research paper for Science, a team of scientists explain that “At the cooler extremes of their distributions, species are moving poleward, whereas range limits are contracting at the warmer range edge, where temperatures are no longer tolerable.” But in places like Tierra del Fuego, at the ‘end of the world’, where climate is extreme and the terrain and seas are difficult, there doesn’t exist an abundance of research detailing current flora and fauna patterns. This lack of data makes it difficult to know exactly how ecosystems are changing and if life is moving towards the poles as temperatures rise.

And thus, we see the entrance of forest ecologist Brian Buma, Chilean ecologist Ricardo Rozzi, Chilean-born forest ecologist Andrès Holz, National Geographic journalist Craig Welch and National Geographic photographer Ian Teh. Awarded a grant from the National Geographic Society, they travelled southward to Isla Hornos (Cape Horn), the southernmost of the islands of South America.

Using the little recent research there was on the island and accounts from explorers like Captain James Cook’s 1775 expedition, these investigators and their crew slowly made their way to the southernmost point in extreme winds, rains, and impenetrable terrain (and managed to squeeze in a bit of sightseeing). They worked their way through terrain vibrant with forest and plants, like “a world created by J.R.R. Tolkien and compressed from above by a giant hand.”

Finally, they reached an outcropping of trees further south than the rest. There lives a 41-year-old tree, known as a Nothofagus betuloides or more commonly as a Magellan’s beech tree. They grow across the globe, above and below the equator, however this one spreads wide and low to the ground due to the extreme weather conditions. Almost a foot in diameter and three feet tall, this tree is a definitive landmark with which to gauge how our warming planet is changing.

Welch explains in his story the weight of the moment by writing, “In a small way, he and Holz have made history. Their work has established a scientific baseline to measure forest migration. It’s also just kind of cool.”

To follow this story from beginning to end, hear the captivating details from the journalist who experienced it, and transport yourself there through the photographs captured, check out National Geographic here!

Food

Food Farmers

Farmers Sustainable Living

Sustainable Living Living Planet

Living Planet News

News